Teachers

-

Hannah HighgateHannah Highgate was an African American woman from Syracuse, N.Y., born around 1820. She and her husband Charles were active in the abolition movement and prepared their six children to be active in advancing the cause of their race. In April, 1864, with the Civil War still unresolved, Hannah wrote to the American Missionary Association regarding her desire to teach in the liberated areas of the South. Her eldest daughter Edmonia was already engaged in this field. “I have long desired,” she wrote, “to do something for my people who have been less fortunate than myself.” She offered her services to the A.M.A. as a matron or assistant teacher. It was only in April, 1865, that Hannah Highgate arrived to teach at Darlington, replacing her daughter Edmonia, who had resigned after starting the school a month earlier in favor of seeking a posting farther south. On July 5, 1865, she reported that the school was “progressing finely.” In August, she was compelled to close the school for a few weeks to allow for the berry picking season. Around the end of that month, Hannah left the school. Although the trustees had wished to remain, she informed the A.M.A. that she was not willing to manage the fall term on her own. This suggests that she may have had previously had the help of her daughter Willella, who is known to have taught at Darlington at some point in 1865. In 1872, the A.M.A. gifted a portrait bust to Hannah Highgate, presumably in recognition of her service. She was unable to come to Philadelphia to collect it in person, and requested it be sent to her current residence in Albany, N.Y.

-

Willella HighgateWillella Highgate was an African American woman from Syracuse, New York. She was the daughter of teacher Hannah Highgate and the sister of teacher Edmonia Highgate. It is unclear exactly when Willella Highgate taught at Darlington. In a December, 1865, letter to the American Missionary Association, Willella announced that she had received an invitation to teach at Louisville, Kentucky. In that letter, she referred to her previous teaching experience as an assistant teacher at Binghamton, N.Y. and Montrose, Pa., and teaching “last summer” at Darlington, Md. Hannah Highgate replaced her daughter Willella in April, 1865, and was still at the school in mid-August, 1865. In September, Mary Watson arrived to take over the school, remaining there until 1869. It is therefore difficult to fit Willella into the timeline as the primary teacher at Darlington. Perhaps Willella acted as assistant to or co-teacher with her mother during all or part of her Hannah's tenure at Darlington, filled in for her during an illness or absence, or succeeded her there briefly before the arrival of Mary Watson. In August of 1868, Willella Highgate wrote to the A.M.A. from Albany, N.Y., expressing interest in teaching in the South again. As this is one of only two letters from Willella in the A.M.A. collection of letters received, it is unclear whether or not the organization employed her again after her brief time in Maryland in 1865.

-

Edmonia HighgateEdmonia Highgate was an African American woman born in Syracuse, New York, in 1844. She was the daughter of Hannah Highgate and the sister of Willella Highgate, both of whom would also teach at Darlington. Before the Civil War her family was involved in the abolition movement. In October, 1864, Edmonia was invited to speak at the Colored Men’s Convention at Syracuse, which was attended by Frederick Douglass. After teaching at schools in Pennsylvania, New York (where she was a school principal), and Virginia, Edmonia came to Darlington in the spring of 1865, supported by the American Missionary Association. As no school building yet existed at Darlington, she taught her students at the Hosanna African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. In an 1864 letter to the American Missionary Association in which she first expressed her desire to teach in the South, she described herself as: “[A]bout twenty years of age and strong and healthy. I know just what self-denial, self-discipline and domestic qualifications are needed for the work and modestly trust that with God's help I could labor advantageously in the field for my newly freed brethren...” Edmonia Highgate taught only about one month at Darlington before she resigned in favor of teaching farther south, where she felt her talents would be better utilized. The American Missionary Association assigned her to a school in New Orleans, Louisiana. She was succeeded as teacher at Darlington by her mother, Hannah Highgate. During the racially motivated New Orleans Massacre of 1866 Edmonia helped care for those wounded. Afterward she moved to Enterprise, Mississippi, where she raised funds for the American Missionary Association. Edmonia Highgate died under mysterious circumstances in New York City in 1870.

-

Mary Gertrude SmallsbeckMary Gertrude Smallsbeck was a teacher at the Fairview School according to a March 9, 1894 article in the Aegis an Intellinger newspaper.[1] The article also mentions that Smallsbeck was the secretary of the “Fairview Tuesday Night Club.” While there were no definitive vital or census records for Smallsbeck, of the two that appeared, one was from the 1860 census and one from the Maryland Births and Christenings, 1650-1995 suggest that Mary Smallsbeck or her parents were born in Guyana.[2] Both records also mention that Mary Smallsbeck’s race was white. This would have made her one or perhaps the only white teacher of a Freedmen’s Bureau school in Harford County during the 19th century.

-

Theresa LyonsTaught at McComas until, according to Baltimore Association actuary John Core, she quit "in disgust." Her McComas assignment likely occurred briefly in January 1869. Before that, Lyons taught in Princess Anne where "no preparation" was made for her, "not even a place for her to board."

-

Maggie J. SorrellTaught at Fallston from at least October 1868 through December 1868. In January 1870, Sorrell was listed as teaching for one month at Middletown in Frederick County.

-

Maggie H. JaquesMaggie H. Jaques taught at the Hopewell/Green Spring school, probably starting in November 1868. In January, 1869, Rosie Sythe took over teaching at Hopewell until June of that year. In the fall of 1869, Jaques returned to Hopewell, submitting reports in October, November, and December.

-

Eliza M. MurryTaught at Fallston from at least April 1869 through June 1869.

-

Richard L. MasonRichard L. Mason appears in the Freedmen’s Bureau Records from January to May of 1869. He takes over as the teacher of the McComas Institute in place of Addie V. Green. Unfortunately, Mr. Mason does not appear in any other records so his background is unclear. He also does not come up in the 1850, 1860 or 1870 U.S. Census Record for Harford County or Maryland in general which suggests that he left the county and perhaps was assigned to teach in another state.

-

Henrietta GilmoreTaught at Hopewell/Green Spring. Listed as living with Hopewell trustee George Washington in 1870 census. In February 1870, Gilmore had to close her school at Cross Keys in Baltimore County and wrote to the Freedmen's Bureau seeking a new assignment. On March 15 of that same year, Gilmore began teaching at Hopewell, continuing through the end of May.

-

Louie C. Waters (Louisa, L.C.)Louisa (Louie) C. Waters was born in Massachusetts around 1850. She taught at the McComas Institute from about October,1869 to June, 1870. Census records indicate that Waters actually lived with George M. McComas while she taught at the school.

-

Mary E. GrantumTaught at Henry Winter Davis/Fallston from October 1869 to at least May 1870.

-

Mary WatsonMary E. Watson (full name Mary Elizabeth Watson) was an African American woman born in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1840. She began teaching in her native state soon after graduating from the Rhode Island State Normal School in 1858. At the end of the Civil War, she applied to the American Missionary Association to obtain a teaching position in the South. In a letter to the Association, she stated her reason for wanting to teach in the former slave states. “My sympathy has always been with the outcast Slave (since the dawn of Emancipation). I feel that God calls me to work for them, to devote my time to those, who have so long been trodden under foot, so long born the heat, and burden of the day; too long been denied” The AMA first sent Mary to teach at Norfolk, Virginia, in early 1865, before transferring her to Darlington, in Harford County, for the fall term of 1865. There was no dedicated school building at Darlington, so, like her predecessor in this position Edmonia Highgate, she initially taught her students at the Hosanna African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. Mary E. Watson proved an able instructor in the classroom and an energetic advocate for her school. Due in part to her efforts, a school building was completed in time for the spring term of 1869. After completing the spring, 1869 term at Darlington, the increasingly limited resources of the American Missionary Association prevented them from continuing to support Watson there on the same terms as before. Instead, they assigned her to teach at Port Deposit, across the Susquehanna in Cecil County. Unlike Harford County, Cecil County had begun partially supporting its black schools, and their teachers, with local taxes. During the period when Watson’s tenure at Darlington was ending and she was trying to secure another position, the AMA was effusive in their praise for her. “The impression she has made will, as long as life last, remain in her scholars. They love and respect her.” They described her as “a light shining in a dark place.”

-

Sarah A. UsherSarah A. Usher was in her mid- to late-twenties when she moved to Harford County to teach at the school in Havre de Grace. While not much is known about the Black teacher before her time in Harford, records indicate that she was born in Jamaica, likely to parents William and Sarah Usher, on June 15, 1843. According to the 1930 census, Usher first migrated to the United States in 1865. She took over leadership of the Anderson Institute from the school’s second teacher, Elizabeth V. Dixon, in October 1869, and remained at the school for only one academic year.

-

Rosie SytheTaught at Hopewell from at least January through June of 1869.

-

Rachel Ann SmithTaught at LaGrange from at least November 1869 through at least May 1870.

-

Ida S. MarshallIda S. Marshall was a free-born African American woman, originally from Massachusetts. Marshall first contacted the Freedmen’s Bureau about a teaching position in March, 1867, writing directly to Commissioner Oliver O. Howard. Her husband, Thomas Marshall, had been General Howard’s personal servant during military operations in South Carolina in 1861. Now Thomas was in ill health, and the couple were living in Baltimore with few friends. General Howard passed her letter to the Bureau’s education superintendent, Rev. John W. Alvord. He responded to Marshall, explaining that the Bureau was not directly involved in the hiring of teachers. He advised her of several aid societies that she might contact for an appointment. She must have had success with the Baltimore Association, because it was that organization that would support the Churchville school from its establishment until April of 1870. Marshall corresponded frequently with the Freedmen’s Bureau, and worked energetically with local white supporters of black education to host public meetings and examinations of her school. In June, 1869, she wrote to Superintendent John Kimball, asking him to support her (unsuccessful) bid to become the U.S. Postmaster at Churchville. By July, 1870, the months of overcrowded classrooms and exposure to inclement weather had taken their toll on Marshall, and she wrote to the superintendent requesting a posting in a state further south, “even Louisiana.” Apparently receiving no response, she traveled north during the summer break to Newport, Rhode Island, where on August 9, 1870, she penned a letter to Rev. John W. Alvord, Freedmen’s Bureau education superintendent and the man who had advised her back in 1867. In that letter, she cited declining salary, exposure, and “other difficulties,” as her reasons for wanting to wanting to teach somewhere other than Maryland, and repeated her desire to relocate to somewhere in the deeper South to continue her work. She was unsuccessful in her efforts, however, and was still teaching at Churchville in early 1871. In April, 1870, support of the school at Churchville transferred from the Baltimore Association (which was ceasing its operations) to the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society. Ida S. Marshall left the school permanently soon after February, 1871. That month, her final monthly report stated that thenceforward the school would be “supported by the county, with a county teacher.” Marshall continued her teaching career elsewhere until at least the mid-1870s at schools in Maryland and South Carolina.

-

M.E. Pauline LyonsM. E. Pauline Lyons (full name Mary Elizabeth Pauline Lyons) was an African American woman from Providence, Rhode Island, who taught at the school at Bel Air (Hendon Hill). Lyons was only 19 years old when she arrived at the school to teach in January, 1870. She was born in New York City, where her father Albro owned a seamen’s outfitting store that doubled as a stop on the Underground Railroad. After their home was destroyed during the Draft Riots of July, 1863, the family relocated to Providence, Rhode Island, where they remained active in advancing the rights of African Americans in that city. Pauline’s elder sister Maritcha would become a prominent educator in New York City, and an associate of fellow educator and activist Ida B. Wells. In keeping with the family mission, the young Pauline embarked upon her own teaching career with the support of the Pennsylvania Branch of the Freedmen’s Union Committee. She replaced the previous teacher at Bel Air, Rachel L. Alexander, for the spring 1870 term. In September, 1870, Pauline Lyons’ job was threatened by the efforts of a local white woman, Esther J. Duvall. Esther was the daughter of Emmett Duvall, a white supporter of black education and associate of George M. McComas. She wrote to Superintendent W. L. Van Derlip in a bid to replace Lyons as teacher, claiming that the trustees of the school desired a replacement for the young Lyons. Esther described the African American people of her area as “’conservative’ in their ideas about youth and inexperience,” and “rather opposed to being subject to a teacher of their own color.” She suggested herself as an appropriate replacement for Lyons. There is no evidence that the Superintendent responded to her letter. There is no evidence of M. E. Pauline Lyons teaching at Bel Air after the September, 1870 letter from Duvall. An 1873 Providence city directory indicates that she was residing at the family home there at that time. Pauline married sometime in the 1870s, and after her husband’s death in 1880, she and her son moved to Oakland, California, where she became a nurse. Her son, Harry Albro Williams, would become a prominent Freemason in the early twentieth century.

-

Joshua G. JordonJoshua G. Jordon began teaching at the Thomas Run/Clark’s Chapel school in April, 1869. Upon his arrival there, Jordon wrote to education superintendent John Kimball reporting that the prospects of the school were, in his opinion, “of the most auspicious nature.” He described the area as thickly populated with freedpeople, all eager for education and “denying every moment of pleasure for study.” Jordon does not appear to have written any further letters to the Bureau. His home state is unknown and he has not been identified with confidence in census records. Jordon’s sponsoring benevolent organization is unclear, but in his letter to Superintendent Kimball he states that he was appointed by the “educational board at Baltimore,” which is probably a reference to the Baltimore Association.

-

Samantha GreenTaught at Perrymansville from October 1869 to at least May 1870. Green appears to have taught again at Perrymansville for the 1879-1880 school year, by which point the school had already been under Harford County control for some time.

-

Addie GreenAddie V. Green is assumed to have been the first teacher at the McComas Institute. Miss Green first appears in the Freedmen’s Bureau Records in the “Records of Complaints, 1865-1872.” A complaint was filed on June 30, 1868 by Addie V. Green, on behalf of a woman named Amy Preston. Preston was living as a servant to Jessie Thompson at Carroll Manor in Harford County. Thompson was refusing to pay Preston wages for her labor, had mistreated her, and refused to let her leave. She requested help from the Bureau in order to get away from Thompson. The record also states that the “complainant is 65 years old and mute.”[1] Green appears in several more Superintendent of Education records and reports from October to December of 1868.[2] She then falls out of the Bureau’s records as a teacher for the McComas Institute. She appears again briefly in July of (year) in a complaint record from Fallston, where she is requesting the assistance from the Bureau to help with the release of four children to the custody of their uncle and aunts as they were being unlawfully kept by a man named Lee Magness.[3] This complaint helps to show how much Miss Green cared for her students and her willingness to advocate for both their education and wellbeing.

-

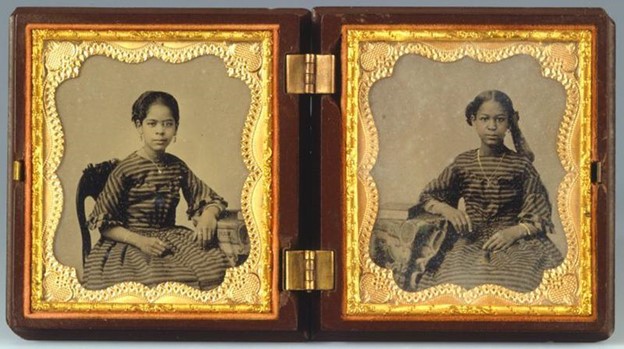

Elizabeth V. DixonWhen Elizabeth V. Dixon arrived in Havre de Grace in the fall of 1868, she likely looked strikingly similar to the young children she had been hired to teach. Records indicate that Dixon was born sometime around 1852, making her 16 or 17 when she opened the school on October 6. Despite her young age, Dixon was tasked with many responsibilities during her time in Harford; over the course of the 1868-1869 school year, for example, she was charged with managing as many as 40 pupils at one time. Additionally, as the town’s only African American educator, it appears Dixon was also responsible for leading the local industrial school, where she taught students how to sew and knit.

-

J.F. Pierpont DicksonJ. F. Pierpont Dickson (also known as J. F. P. Dickson or Julie Dickson) was an African American woman who taught at the Thomas Run/Clark’s Chapel school. The exact date of her assignment to this school is unknown, but she filed monthly teacher’s reports from January to June, 1870. Previously she had taught at a school in Dorcester County, Maryland. Dickson’s sponsoring benevolent society was the New England Freedmen's Aid Society (aka the New England Branch of the Freedmen’s Union Committee). Her home state is unknown and she has not been identified with confidence in the U.S. census. In January, 1870, Dickson sent a letter directly to Freedmen’s Bureau Commissioner Oliver O. Howard, seeking redress for an incident that took place in October of 1869, when Dickson was teaching in Dorcester County. She was boarding a train with other passengers, when the brakeman, Charles Stewart, approached and told her that she must ride in the smoking car. Dickson refused, whereupon Stewart called over the conductor, Daniel Muze, and again insisted that the car she was boarding was “for white folks” only. As this was happening, Stewart opened the door for some white passengers to enter, and as Dickson attempted to enter with them, he grabbed “violently” by the arm, tearing her cloak and gloves. He dragged her away from the train and threw her against the platform railing. Still, Dickson refused to board the smoking car. She threatened to sue, and was told by Stewart to “sue and be damned.” She ended up standing on the open area at the end of the train car for the journey, and in her letter she told Howard that she was still suffering from the ill effects of her resulting exposure to the cold. There is no evidence that the Bureau took any action in response to her letter among the records of the commissioner's office.

-

Phenia C. CrisfieldPhenia C. Crisfield was a teacher supported by the Pennsylvania Freedmen’s Relief Association, an aid society based in Philadelphia. In October, 1869, Crisfield was sent by the Association to Darlington, Maryland, to replace beloved teacher Mary Watson, whose supporting organization, the American Missionary Association, could no longer afford to fund her there. Crisfield taught at the school until April, 1870. At that time, the Pennsylvania Freedmen’s Relief Association ceased supporting teachers and schools in the South. She was then sent to teach a school at New Market, in Frederick County, Maryland. Phenia C. Crisfield has not been identified in the U.S. census. Her home state is unknown.

-

John H. CamperTaught at Forest Hill for most of 1869 and at least through May 1870. Wrote to John Kimball in June 1869 about the burning of the Mt. Tabor school in Anne Arundel County. Camper appears to have taught at Fairview for the 1872-1873 school year, by which point Fairview was already under Harford County control. Camper taught again at Fairview for the 1873-1874 school year.

-

Mary J.C. AndersonMary J.C. Anderson was an African American teacher who taught at the Havre de Grace colored school from at least 1865 to 1868. Anderson’s life before she moved to Maryland is not fully known, but she was likely born in Pennsylvania in 1845 and named after her mother, Mary Anderson. By 1860, the younger Anderson and her family, which consisted of 7 siblings, were living in Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward. While it is unclear what year she left Pennsylvania, it is known that by 1864, Anderson was spending time in Harford County, Maryland. There she secured subscriptions to the Philadelphia Christian Recorder among several Harford residents, including William Bond, Stephen Wilson, and Joseph Peaco.

-

Rachel L. AlexanderRachel L. Alexander was an African American woman from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, who taught at the Bel Air/Hendon Hill school. On September 29, 1869, Superintendent John Kimball wrote to Alexander at her home in Philadelphia, directing her to go to Hendon Hill to teach. She arrived there on October 5, 1869, and wrote to Supt. Kimball the next day to inform him that she did not plan to begin teaching until the following Monday, owing to the schoolhouse not being quite finished. Alexander taught at Hendon Hill for less than three months, leaving the school on Christmas Eve, 1869, after the end of the fall term. In January, 1870, she wrote to her sponsor, the Pennsylvania Branch of the Freedmen’s Union Committee, asking if she was to be posted to a new school. It is unclear why she did not return to Hendon Hill for the spring term.