The School at Bel Air, Also Known as Hendon Hill

The Freedmen’s Bureau supported school at Hendon Hill, outside the county seat of Harford County, Bel Air, opened in late 1869. While the place name Hendon Hill has fallen out of use, evidence indicates that it was located about one and a half miles west of Bel Air, on Vale Road.[1] Hendon Hill would serve as the school for the Bel Air area, appearing in Freedmen’s Bureau records as both Hendon Hill and Bel Air, until the opening of a separate school in the town itself sometime before 1881.

The earliest evidence found relating to this school is dated August 27, 1867. On that date the Baltimore Association sent the Maryland and Delaware Assistant Commissioner, General Gregory, a list of materials needed to build a new school at Hendon Hill. Accordingly, on September 28, 1867, Bureau Special Agent Samuel J. Wright was ordered to furnish materials, labor, and furniture for the school. This was a start, but the process of completing the schoolhouse would be a long one.

As of October, 1868, the school was still not incomplete. On the 21st of that month, George M. McComas, the most prominent white patron of black education in Harford County, wrote to John Kimball, the Freedmen’s Bureau Superintendent of Education for the state, inviting him to a fundraising fair at Hendon Hill to be hosted by the trustees of the school.[2] He referred to trustee George Dougherty as “a first rate man” who had given $100 of his own money to the cause of building the school.[3] Kimball vacillated and ultimately did not attend the fair. On November 3, McComas wrote to him that the fair had taken place without any speeches, and that the people had asked when the Superintendent might visit them and if the Bureau would aid them further. There is no record of a response from Kimball, but on November 11 he wrote to John Core of the Baltimore Association with a list of proposed new schools that the Baltimore Association might support. Hendon Hill was among them.

On January 19, 1869, George McComas wrote again to Kimball, this time reporting the results of a meeting he had had with the trustees at Hendon Hill. McComas described them as “despondent.” A deed for the property (which the Freedmen’s Bureau now required evidence of before helping to start schools) had still not been executed but soon would be. The trustees had also incurred so much debt that they had decided not to continue construction until they had eliminated that debt. McComas assured the trustees that help would come, and that desks could be supplied to them with the help of the Bureau. McComas also gave the dimensions of the schoolhouse: 40 x 24 feet. Superintendent Kimball responded, asking McComas if desks might be made locally to the school, and what it would cost to have them made.

In February, 1869, the promised deed was finally signed and McComas sent a copy along to Bureau headquarters in Washington. Along with the deed, McComas wrote a note to Supt. Kimball on the subject of school furniture. He reported that “Soper” benches could be made and delivered for $4 each, but that the school would require about twenty desks and additional benches from the Bureau. The following day Kimball wrote to McComas that he had asked the Assistant Commissioner for $100 to fund the remaining work at Hendon Hill.

As of June, 1869, the school remained incomplete. On the 21st of that month, George McComas wrote to Supt. Kimball, telling him that the trustees were prepared to receive a teacher, and inquiring about the matter of school furniture, which had evidently still not been addressed. On August 1, 1869, McComas again invited Kimball to speak at an event at Hendon Hill to be held on August 18. Once again Kimball did not attend, but representatives of the local media did. On August 20, the local newspaper The Aegis reported on the meeting at Hendon Hill, listing the speakers and adding no editorial commentary.

On August 28, Kimball informed McComas that he had acquired the $100 in funding for the school. He specified that the money must be used for the building, and not directly for furniture.[4] With this money finally in hand, the school progressed rapidly. Receipts from early September, 1869, include payments for carpentry work, shingles, and plastering. But the equipping of the school with desks was proving to be unusually difficult. Later in the month, McComas informed Kimball that desks had still not been arranged for, and that, while the material for desks would not be expensive, the cost of having them made would be more so.

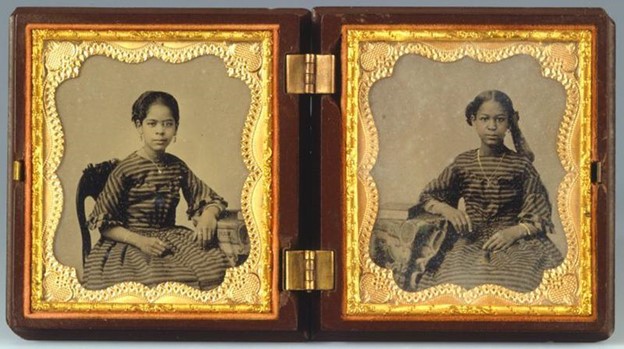

By the end of the month the school was at last deemed ready to receive a teacher. On September 29, Supt. Kimball wrote to Rachel L. Alexander, of Philadelphia, directing her to go to Hendon Hill to teach. Alexander was an African American teacher sponsored by the Pennsylvania Branch of the Freedmen’s Union Committee, which, along with other benevolent societies, coordinated with the Freedmen’s Bureau in supplying schools with teachers. She arrived at Hendon Hill on October 5, 1869, and wrote to Supt. Kimball the next day to inform him that she did not plan to begin teaching until the following Monday, owing to the schoolhouse not being quite finished.

Three of Rachel Alexander’s monthly school reports are on file in the Freedmen’s Bureau archive. In October, 1869, she reported 19 students enrolled, and her school in a “prosperous condition.” Her report for November, 1869, indicates that she had twenty students enrolled, and she remarked that she had “all prospects of a fine school this Winter.” Her report for December, 1869, indicated an increase to twenty-eight students enrolled. Six out of her eight female students were engaged in an “industrial school” to learn sewing.

Rachel Alexander taught at Hendon Hill for less than three months, leaving the school on Christmas Eve, 1869, after the end of the fall term. In January, 1870, she wrote to her sponsor, the Freedmen’s Union Committee, asking if she was to be posted to a new school. It is unclear why she did not return to Hendon Hill for the spring term.

Alexander’s replacement was M. E. Pauline Lyons, who was only 19 years old when she arrived to assume her duties in January 1870. Lyons was originally from New York City, where her parents owned a house that was a stop on the Underground Railroad. During the infamous draft riots of 1863 the house was burned by the mob, and the family relocated to Providence, Rhode Island. Three of the family’s daughters became teachers, with Pauline’s sister Maritcha destined to become a prominent educator and civil rights activist in New York City.

Four monthly reports survive for the period of M. E. Pauline Lyons’ tenure at Hendon Hill, spanning January to May, 1870. Her enrollment during this period ranged between 17 and 24 students. Like Alexander, she maintained an industrial school in which students were trained to make their own garments. In her March report, Lyons reported that the school had recently received desks and a new stove, courtesy of George M. McComas. Incredibly, it seems that Hendon Hill managed without desks until this time.

In September, 1870, Pauline Lyons’ job was threatened by the efforts of a local white woman, Esther J. Duvall. Esther was the daughter of Emmett Duvall, a supporter of black education and associate of George M. McComas. The Duvalls lived a short walk away from the Hendon Hill school. Now Esther wrote to Supt. Van Derlip in a bid to replace Lyons as teacher. She claimed that the trustees, including George Dougherty, were desirous of a replacement for the young Lyons. Esther described the African American people of her area as “’conservative’ in their ideas about youth and inexperience,” and “rather opposed to being subject to a teacher of their own color.” She suggested herself as an appropriate replacement for Lyons. There is no evidence that the Superintendent responded to her letter.

There are no further records in the Bureau archive regarding Hendon Hill after Esther J. Duvall’s letter. At some point after this date the school closed. An Aegis article dated December 15, 1881, reported on the effort of both black and white citizens to encourage the County Commissioners to reopen the school at Hendon Hill. The commissioners declined, but lists of county schools in the Aegis later in the decade indicate that the school was eventually put back into operation.

By James Schruefer

[1] Doug Washburn, “The Colored Schools of Harford County: Separate and Equal? Part 1,” Harford Historical Bulletin 101 (Summer/Fall 2005), 5.

[2] The trustees were George Dougherty, Edward Hall, Preston Lee, William Morgan, and William A. Ruff. Only Dougherty was a landowner in 1870. (U.S. Census)

[3] George Dougherty possessed only $100 in personal estate in 1870, so this was a substantial contribution on his part. (U.S. Census)

[4] Why the funds could not be used for furniture even though the Bureau supplied furniture to many other places, is unclear. Also unclear is why Kimball was so focused on having the desks manufactured locally rather than supplying them from Bureau stocks in Baltimore, which was done for other Harford County schools. The Bureau's supply may have run out.